Announcing the First Results from Daya Bay: Discovery of a New Kind of Neutrino Transformation

BEIJING; BERKELEY, CA; and UPTON, NY – The Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment, a multinational collaboration

|

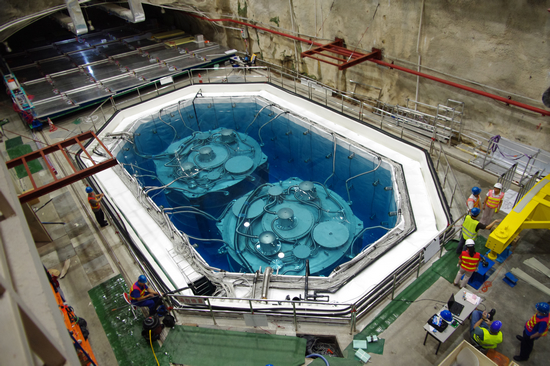

| Daya Bay Collaboration discovers a new kind of neutrino transformation (PIc/Daya Bay Collaboration) |

Traveling at close to the speed of light, the three basic neutrino “flavors” – electron, muon, and tau neutrinos, as well as their corresponding antineutrinos – mix together and oscillate (transform), but this activity is extremely difficult to detect. From Dec. 24, 2011, until Feb. 17, 2012, scientists in the Daya Bay collaboration observed tens of thousands of interactions of electron antineutrinos, caught by six massive detectors buried in the mountains adjacent to the powerful nuclear reactors of the China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group. These reactors, at Daya Bay and nearby Ling Ao, produce millions of quadrillions of elusive electron antineutrinos every second.

The copious data revealed for the first time the strong signal of the effect that the scientists were searching for, a so?called “mixing angle” named theta one-three (written θ13), which the researchers measured with unmatched precision. Theta one-three, the last mixing angle to be precisely measured, expresses how electron neutrinos and their antineutrino counterparts mix and change into the other flavors. The Daya Bay collaboration’s first results indicate that theta one-three, expressed as sin2 2 θ13, is equal to 0.092 plus or minus 0.017.

“This is a new type of neutrino oscillation, and it is surprisingly large,” says Yifang Wang of China’s Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP), co-spokesperson and Chinese project manager of the Daya Bay experiment. “Our precise measurement will complete the understanding of the neutrino oscillation and pave the way for the future understanding of matter-antimatter asymmetry in the universe.”

Neutrinos, the wispy particles that flooded the universe in the earliest moments after the big bang, are continually produced in the hearts of stars and other nuclear reactions. Untouched by electromagnetism, they respond only to the weak nuclear force and even weaker gravity, passing mostly unhindered through everything from planets to people. The challenge of capturing these elusive particles inspired the Daya Bay collaboration in the design and precise placement of its detectors.

|

| The antineutrino detectors are submerged in pools of water to shield them from radioactive decays in the surrounding rock. (pic/ DayaBay Colaboration) |

The Daya Bay experiment counts the number of electron antineutrinos detected in the halls nearest the Daya Bay and Ling Ao reactors and calculates how many would reach the detectors in the Far Hall if there were no oscillation. The number that apparently vanish on the way (oscillating into other flavors, in fact) gives the value of theta one-three. Because of the near-hall/far-hall arrangement, it’s not even necessary to have a precise estimate of the antineutrino flux from the reactors.

“Even with only the six detectors already operating, we have more target mass than any similar experiment, plus as much or more reactor power,” says William Edwards of Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, the U.S. project and operations manager for the Daya Bay Experiment. Since Daya Bay will continue to have an interaction rate higher than any other experiment, Edwards explains, “it is the leading theta one-three experiment in the world.”

The first Daya Bay results show that theta one-three, once feared to be near zero, instead is “comparatively huge,” Kam-Biu Luk remarks, adding that “Nature was good to us.” In coming months and years the initial results will be honed by collecting far more data and reducing statistical and systematic errors.

“The Daya Bay experiment plans to stop the current data-taking this summer to install a second detector in the Ling Ao Near Hall, and a fourth detector in the Far Hall, completing the experimental design,” says Yifang Wang.

Refined results will open the door to further investigations and influence the design of future neutrino experiments – including how to determine which neutrino flavors are the most massive, whether there is a difference between neutrino and antineutrino oscillations, and, eventually, why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe – because these were presumably created in equal amounts in the big bang and should have completely annihilated one another, the real question is why there is any matter in the universe at all.

“It has been very gratifying to be able to work with such an outstanding international collaboration at the world's most sensitive

|

| The cylindrical antineutrino detectors (pic/ Daya Bay Collaboration) |

“This is really remarkable,” says Wenlong Zhan, vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and president of the Chinese Physical Society. “We hoped for a positive result when we decided to fund the project, but we never imagined it could come so quickly!”

“Exemplary teamwork among the partners has led to this outstanding performance,” says James Siegrist, DOE Associate Director of Science for High Energy Physics. “These notable first results are just the beginning for the world's foremost reactor neutrino experiment.”

The Daya Bay collaboration consists of scientists from the following countries and regions: China, the United States, Russia, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The Chinese effort is led by co-spokesperson, chief scientist, and project manager Yifang Wang of the Institute of High Energy Physics, and the U.S. effort is led by co-spokesperson Kam-Biu Luk and project and operations manager William Edwards, both of Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, and by chief scientist Steve Kettell of Brookhaven.

Further readings:

Observation of electron-antineutrino disappearance at Daya Bay

A side-by-side comparison of Daya Bay antineutrino detectors

Contact information:

Yifang Wang, co-spokesperson, IHEP, +86-10-88236076, yfwang@ihep.ac.cn

Kam-Biu Luk, co-spokesperson, Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley, 510?486-7054, 510-642-8162, k_luk@lbl.gov

Tongzhou Xu, IHEP Public Affairs, +86-10-88235008, xutz@ihep.ac.cn

Paul Preuss, Berkeley Lab Public Affairs, 510-486-6249, paul_preuss@lbl.gov

Justin Eure, Brookhaven Public Affairs, 631-344-2347, jeure@bnl.gov

Notes: The collaborating institutions of the Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment are Beijing Normal University, Brookhaven National Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Charles University in Prague, Chengdu University of Technology, China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group, China Institute of Atomic Energy, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Dongguan University of Technology, Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, University of Hong Kong, Institute of High Energy Physics, Illinois Institute of Technology, Iowa State University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Nanjing University, Nankai University, National Chiao-Tung University, National Taiwan University, National United University, North China Electric Power University, Princeton University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Shandong University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shenzhen University, Siena College, Tsinghua University, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Cincinnati, University of Houston, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Science and Technology of China, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, University of Wisconsin-Madison, College of William and Mary, and Sun Yat-Sen (Zhongshan) University.

For more information, visit