Rise of the Physics Powerhouse

Opening the latest Physics World special report on China, Matin Durrani takes stock of the challenges and opportunities for the country’s physicists

“China is a different country from when I first left,” says Xinchou Lou, director of experimental physics at the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) in Beijing. Having returned to China in 2012 after almost three decades in the West, including 18 years at the University of Texas, Lou is one of a new breed of researchers tempted back to China by the huge new opportunities on offer – in his case by the country’s plans to build a 240?GeV Circular Electron–Positron Collider (CEPC). This giant facility would be 50?km – or possibly even 100?km – in circumference and put China at the forefront of particle physics.

If all goes well, construction of the collider will start in the mid-2020s, with data rolling in by the end of the decade, letting researchers study the properties of the Higgs boson in detail. But typical of its grand ambitions, China is already thinking about upgrading the machine to form a proton–proton collider with a centre-of-mass energy of up to 100?TeV. It would outperform CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, which operates at just 13?TeV. “Building a proton–proton successor to the CEPC would totally transform physics in China,” Lou says. “It wouldn’t be a quantum leap but a multiple quantum leap.”

The CEPC – and its successor – are illustrative of the stream of new facilities coming on line in China over the next few years. The Five-hundred Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) is ready for business this month in the south of the country, while the China Spallation Neutron Source in Dongguan is due to open next year. Other big facilities under way include the China Jingping Underground Laboratory, which has plans to study neutrinos, dark matter and stellar reactions (see “World beaters”) .

China’s space programme is also going from strength to strength. As well as a series of space-science probes (see “Plotting a strategy for space”), the country will send its first lunar sample-return mission next year and land the world’s first craft on the far side of the Moon in 2018. Meanwhile, the China Institute of Atomic Energy is working on an ambitious “fast” reactor programme, which seeks to build a new generation of nuclear plants that reuse waste as fuel. An experimental fast reactor opened in 2011, with a demonstration plant set to be built by 2023 and a commercial facility by 2030.

All these projects – and many others besides – are testament to China’s growing realization that research should not just be about meeting short-term goals, such as high-speed trains, solar panels or new drugs, but also investing in blue-skies research that will yield long-term dividends. Spending on R&D as a fraction of gross domestic product (GDP) has more than doubled since 2000 to 2.1% in 2014 according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The budget of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), which funds basic research, has risen 300-fold over the last 30 years and now stands at ¥24.8bn ($3.8bn) per year (see “A vision for the future”), with physics receiving about ¥1bn annually. According to Elsevier’s Scopus database, Chinese researchers accounted for almost 19% of all papers in 2015. Meanwhile, in June China’s president, Xi Jinping, told a meeting of the great and the good from Chinese science that the country should be a leading scientific innovator by 2030 and a dominant scientific country by 2049.

Speaking to Physics World, Wenlong Zhan, who is president of the Chinese Physical Society, identifies iron-based superconductivity, quantum information and communication, and neutrino science as three key strengths for Chinese physics. “These were picked out by the government in its 13th five-year plan, which was published in March,” says Zhan, who spent eight years from 2008 as vice-president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which has more than 100 research institutes nationwide. “I am optimistic about the future of physics,” he adds.

Growing pains

Despite the expansion of Chinese science, the country faces challenges. Less than 5% of its total R&D budget, for example, goes on basic research and, while there are plans to double the proportion to 10% by 2020, that figure is still less than in the US, which ploughs back 17.6% of its R&D spending into blue-skies science. There have also been question marks over the quality and impact of many of those publications, though policies surrounding scientific evaluation are slowly changing.

| Building China’s Silicon Valley | ||

|

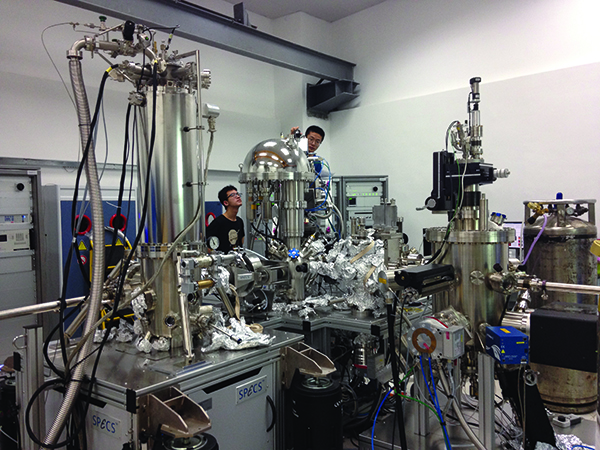

As well as boosting industry, the local government is also making Shenzhen a scientific powerhouse. In 2011 the South University of Science and Technology of China (SUSTC) opened its doors, featuring 12 departments. In 2015 the university had nearly 1000 students – a 50% increase from the year before – with officials hoping that the numbers will rise to 8000 by 2018. Despite being just five years old, the physics department at SUSTC is already very active. It currently focuses on experimental and theoretical condensed-matter physics, with around 20 undergraduate students each year – a number that is expected to rise as the department expands into other areas of physics. The university is not short of cash either as each of the 26 physics professors has around ¥6.5m (m) to build up their own lab. Indeed, the department already boasts an impressive number of experimental facilities, from scanning tunnelling microscopes to a ¥650,000 clean room that allows researchers to build silicon-based devices. As well as basic research, the university is also expected to play its part in fostering collaboration and spurring innovation. It neighbours a Chinese Academy of Sciences institute for technology transfer as well as a technology park of hi-tech companies and start-ups. “The government wanted to build a university not only to carry out research but also support neighbouring hi-tech companies,” says SUSTC physicist Gan Wang. “The idea is to build a Silicon Valley.” |

Many of China’s 2500 universities have cut the fraction of a researcher’s salary based on number of papers, focusing on rewarding merit instead. The education ministry is also looking to give extra cash to top universities rather than spreading money more thinly around lots of average institutions. That could be good news for Peking University, the University of Hong Kong and Tsinghua University in Beijing, which came second, fourth and fifth respectively in the 2015/16 Times Higher Education list of top universities in Asia.

Scientific misconduct is another challenge for Chinese science, although an anti-misconduct campaign begun in 2006 by the China Association for Science and Technology, the education ministry and the NSFC is paying dividends. Writing in Nature (534 467), Wei Yang – president of the NSFC – says that the proportion of alleged misconduct cases in grant proposals submitted to it have halved to just 1% since the campaign started. “The culture of new researchers is changing from ‘why not cheat’ to ‘it is not worth getting caught’,” he says. As Yang adds in an interview with Physics World (see “A vision for the future”), he wants to “raise the overall reputation of Chinese research work”.

In a press briefing earlier this year, Yuan Guiren, minister of education, admitted that the Chinese higher-education system is “not optimal”, but he focused on another problem – that there are “too many institutions focusing on academic and theoretical areas while few focus on practical skills”. This has led to a skills-shortage paradox, in which, as Guiren puts it, “college graduates find it hard to get a job while employers find it hard to recruit a qualified employee”. About 200 smaller, local colleges are now taking part in a pilot programme to focus on more applied courses, especially science and engineering. “We need to cultivate more skilled front-line talent in the transformation for our real economy,” Guiren says.

Attracting talent

Staff on the programme are allowed to apply for grants – something foreigners cannot otherwise do – and are given generous welfare support for them and their families. Xinchou Lou at IHEP is one physicist to have come to China through the programme. Another is Barry Sanders from the University of Calgary in Canada, who gives his advice on how foreign researchers can collaborate with their Chinese counterparts (see “Cultivating good relations”).

But despite such packages and rising research funding, attracting overseas researchers to work in China is not always easy. At one level, it is simply a question of geography: China is a long way from the scientific powerhouses of Europe and the US. But there are cultural barriers too. Some physicists who have never visited China worry about having to learn the language, while others wonder what life might be like in a Communist country. Many scientists who move to China therefore either came originally from the country or have partners or family who are Chinese.

“Recruitment can be hard for non–Chinese foreigners and even persuading them to apply can be tricky,” admits Richard de Grijs, a faculty member at the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Peking University in Beijing. Having moved from the UK to China in 2009, de Grijs says that Beijing has particular problems of its own too – housing is expensive on the private market and air quality can be poor, especially in winter when lots of coal is burned.

But de Grijs says that environmental conditions have improved in the capital in recent years and food and transportation in the country are cheap too. “Overall I would say China is a fantastic place, especially for students and postdocs wishing to come for two or three years,” says de Grijs, who is a representative in China for the Institute of Physics, which publishes Physics World. “Often the best way to show outsiders what China has to offer is for us to simply invite them over to see for themselves.”

Source: Physics World

For the original Link:

http://live.iop-pp01.agh.sleek.net/physicsworld/reader/#!edition/editions_China-2016/article/page-15165